As climate conditions shift, how should energy modeling tools evolve to better address transient thermal comfort conditions in warming climates?

-Seeking information

Dear Seeking,

As global warming intensifies, achieving thermal comfort becomes increasingly challenging. In many areas, it’s becoming increasingly common for temperatures to exceed what we’d consider comfortable, placing heat stress on pedestrians and exposing populations to greater health risks. These conditions directly threaten the viability of walkable, pedestrian-oriented urban design that is critical for sustainable development.

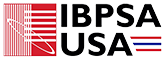

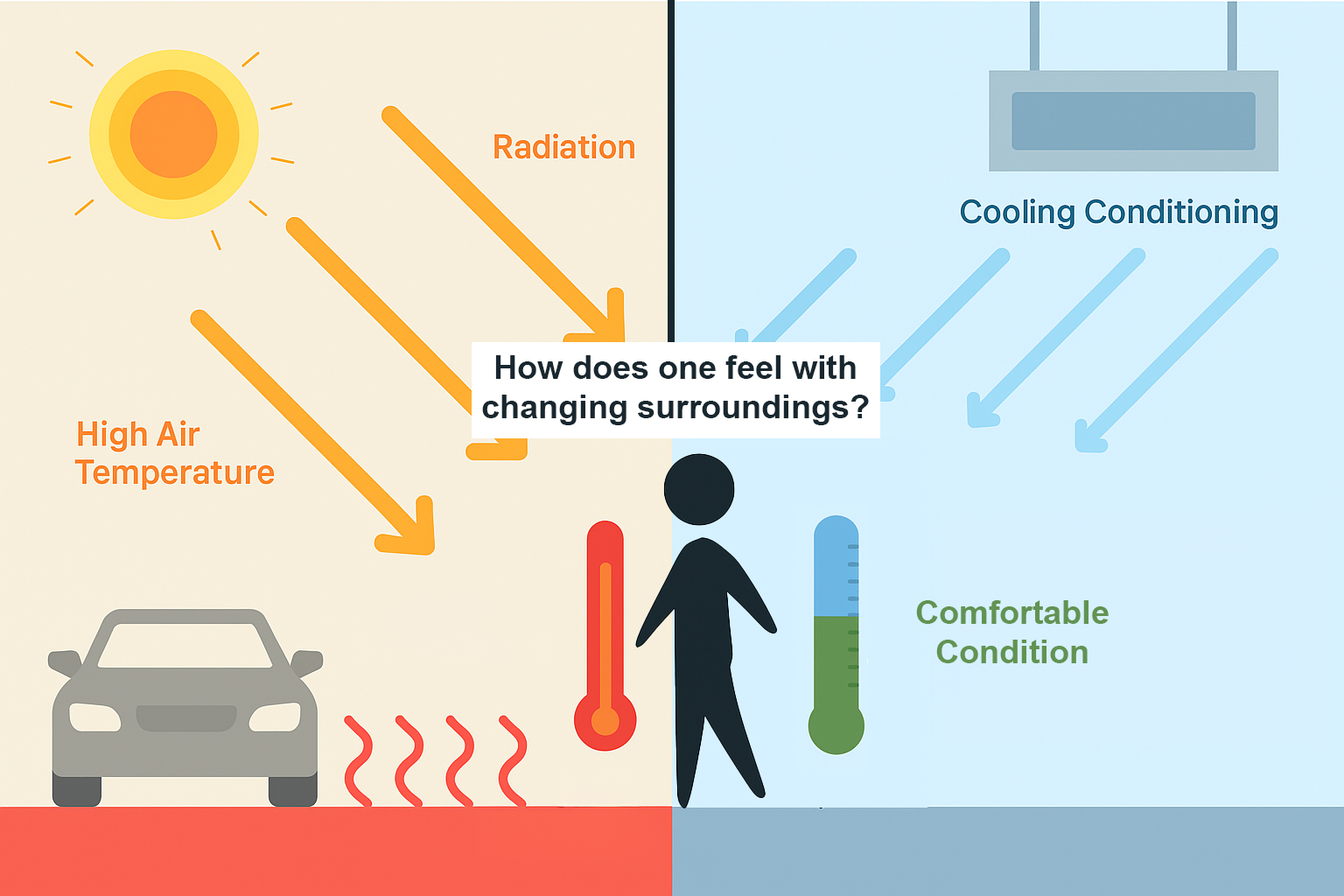

At the same time, as we incorporate more passive or semi-passive strategies, such as natural ventilation or localized cooling like fans, and move away from purely mechanical air conditioning, indoor environments become more dynamic and responsive to natural conditions. In transitional spaces like lobbies and corridors, people experience quick shifts in thermal conditions, such as air temperature, radiant temperature, and air movement, as they move between outdoor and indoor environments. Such transient changes can hardly be captured by steady-state models, which assume the body has already reached heat balance with its surroundings. As a result, traditional metrics fail to capture how occupants perceive and adapt to environmental changes over time. To address this, energy modeling tools should evolve to incorporate transient thermal comfort models that reflect how humans adapt to fluctuating microclimate in a fine temporal resolution. These models will allow designers to evaluate how comfort changes as people move through different spaces or experience short-term deviations.

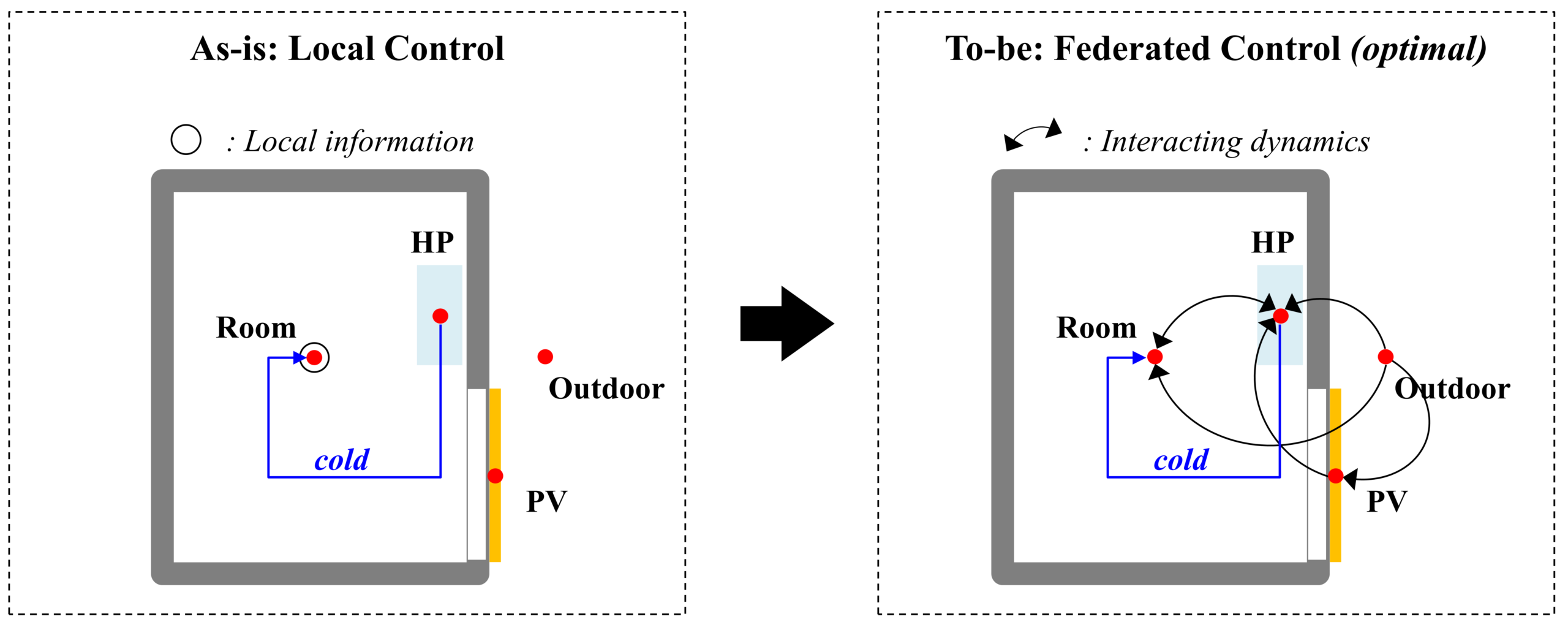

To enable more accurate simulation of transient conditions across various sequences and to support the assessment of dynamic environments, modeling tools should evolve to address the following aspects:

- Path-based Simulation: Picture someone leaving a sun-baked plaza and stepping into a cool lobby, or moving from a perfectly conditioned interior into a courtyard filled with vegetation and mist. Along the path, the thermal sensation of occupants changes continuously, influenced by both environmental transitions and the bodies’ response. Transient thermal comfort is inherently path- and time-dependent, as it evolves over time with the sequence of spaces and conditions a person experiences. At a collective level, understanding transient comfort requires analyzing representative occupant trajectories of how occupants move through spaces to capture typical thermal experiences. To support this, energy modeling tools should enable multi-path simulations that capture the temporal evolution of comfort along diverse activity routes and allow for aggregated spatial analyses. Such capabilities can locate critical areas where existing strategies fail to maintain acceptable comfort and where design should pay attention to.

- Initial Body Condition: The experiences between an individual exiting a warm vehicle and another entering from a cold outdoor environment into a parking lot can be largely different. Representing such differences requires accurately initializing body states to reflect variations in occupants’ initial thermal conditions. Most models define this state through physiological parameters, such as core, mean, or local skin temperatures, of which the specification often demands strong domain expertise. For example, the mean skin temperature of a person exiting a heated vehicle may be around 34 °C, while someone coming from the cold outdoors may have a mean skin temperature lower than 33 °C. Modeling frameworks should either include a pre-run steady-state simulation to approximate these conditions or direct parameter inputs with well-calibrated default values to establish realistic starting points for transient comfort analysis.

- Microclimate: Consider, for example, two people only a few meters apart, one standing in the shade under a tree and another directly under the noon sun, or someone sheltered behind a wall versus another standing against the open strong wind. Despite being in almost the same location, their thermal experiences can differ dramatically due to radiation and air movement. Transient thermal comfort has high temporal and spatial resolution, requiring a detailed understanding of the surrounding microclimate to then accurately simulate human thermal responses. As design increasingly focuses on passive or semi-passive strategies, like shading or wind control, it becomes essential for modeling tools to capture microclimatic parameters with sufficient fidelity. While parameters like mean radiant temperature, air temperature, and humidity are relatively straightforward to obtain or estimate, local air velocity often requires computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis, a physics-based numerical method used to simulate how fluid (including air) moves.These simulations, however, are typically computationally demanding. To address this, modeling frameworks should (1) incorporate accurate CFD-based airflow simulation when air movement significantly influences comfort with optional optimized computation by pre-calculating and storing results in a queryable database or (2) integrate validated, AI-powered models to predict local wind conditions at nearly real-time.

As climates grow more extreme and design increasingly emphasizes pedestrian-oriented planning and passive strategies, modeling must evolve to capture a more nuanced understanding of thermal sensation under fluctuating conditions. In environments where thermal equilibrium is hardly achieved, current modeling practices become insufficient. Although research on transient thermal comfort has advanced a lot recently, its integration into everyday design and engineering practice remains limited. Strengthening these capabilities will allow practitioners to identify where comfort breaks down, evaluate strategies to restore it, and design spaces that remain livable and resilient in a warming world.

Amber Jiayu Su

Graduate Researcher, Sustainable Design Lab MIT

amberjys@mit.edu